Electronic english version since 2022 |

The newspaper was founded in November 1957

| |

|

Number 2 (4700) |

FLNP - 65

And it all started almost half a century ago...

We continue the series of publications about leading staff members of the Laboratory that started on the eve of the 65th anniversary of FLNP. Today, FLNP chief researcher Anatoly Balagurov is recalling his path to science, the history of the establishment of the Laboratory for Condensed Matter Research. He started working in the Laboratory in 1968 after having graduated from the Physics Department of Moscow State University with a degree in physics.

Learning about Dubna

In my fourth year at the university, I was assigned to the Department of Elementary Particles that was based at the branch of the SINP MSU in Dubna and from the beginning of 1966, my studies continued in Dubna. In addition to our department, students from the Department of Theory of the Atomic Nucleus studied at the branch. At that time, both departments were very popular among students of the Physics Department; in total, about 30 people from our course continued their studies in Dubna. We lived in a hostel on Leningradskaya, next to the branch and listened to lectures by such famous scientists as B.M.Pontecorvo, M.G.Meshcheryakov, S.M.Bilenky, M.I.Podgoretsky, A.A.Tyapkin, V.G.Soloviev and others. They lived amicably, cheerfully and sportily, organized their own football team, entered the city championship and performed quite well. We also studied well, the people were mostly not without abilities, many from our course and above all, from two Dubna departments were subsequently invited to work at JINR. Among them that later became very famous scientists were D.Bardin, A.Kulikov, G.Mitselmacher, V.Pervushin, N.Piskunov, V.Priezzhev, A.Sisakyan, M.Smondyrev, G.Shelkov and others.

The Department of Elementary Particles was headed by Bruno Pontecorvo (we addressed him as Bruno Maksimovich), a brilliant physicist and a cheerful, passionate person. In between lectures, he played table football with us in the hall using coins, demonstrating amazing sleight of hands, performing tricks with the same coins, for example, rolling a nickel on the table, pushing it alternately with his hands. Bruno Maksimovich was an absolutely accessible person, answered questions with pleasure and did not refuse to recall some moments of his turbulent life. It is worth noting that today, I live in Dubna on Pontecorvo Street.

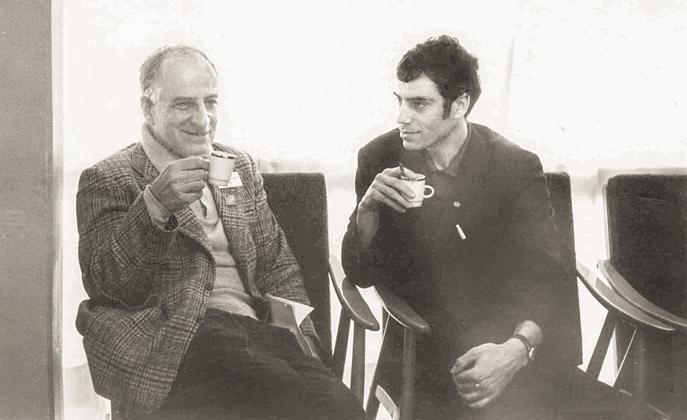

B.Pontecorvo and A.Balagurov during a break between lectures

The bias in lectures and seminars for students of the Department of Elementary Particles was naturally towards high energy physics, however, when it came time to choose which of the institute's laboratories to do my thesis in, I chose the Laboratory of Neutron Physics, where there were no high energies, in principle. This happened mainly due to the reception we were given at FLNP, when the whole group of us went to learn about the laboratories. If at DLNP and FLNR we were simply taken around the experimental facilities, telling us something as we went, then at FLNP, we were met by F.L.Shapiro, then the deputy director that sat us down in his office and talked in detail for nearly an hour about what papers could be as thesis topics, who of the FLNP employees will be the leader, why these topics and leaders are remarkable and so on. I especially liked one of the potential topics, "Measuring the amplitude of neutron-electron (n-e) interaction" for its originality, fundamental nature and the fact that it was still close to the physics of elementary particles. I had an interview with Yu.A.Aleksandrov, the supervisor of this paper, we seemed to like each other and since autumn 1966, I spent several days a week at FLNP, learning about the methodology and carrying out all sorts of, at first, small tasks.

The technique proposed by Yu.A.Aleksandrov for measuring the amplitude of the n-e interaction was very original and promising, but required a fairly large amount of preliminary research. In particular, it was necessary to know the neutron coherent scattering lengths for tungsten isotopes with good accuracy. This experiment became the immediate topic of my thesis, that is, I was entrusted with its implementation, processing and analysis of experimental data. In principle, the experiment itself was not very complicated - it was necessary to measure the diffraction spectra of four samples enriched in different isotopes of tungsten, yet its implementation and especially the analysis of the data required great care and ingenuity. I had a hard time, first of all, because I simply did not know anything about neutron diffraction, since it was not included in our courses. Moreover, this technique was completely new at FLNP and few people could say anything constructive about it. I mastered the technique as I went along, reading mainly original articles in scientific journals that was also not easy, since my level of English was rather weak. Nevertheless, the experiments were carried out successfully, the proposed data processing algorithm worked successfully, the results were quite reliable and it was possible to write a thesis and think about what to do next.

I defended my thesis perfectly, although I did not fully answer one of F.L.Shapiro's insidious questions about the details of temporal focusing in time-of-flight diffraction. Even before my defense, Fedor Lvovich offered to speak at a laboratory seminar with a report on the references and he himself gave the topic "Measurement of the electric charge of a neutron". The topic sounded somewhat paradoxical, it is known that the neutron is a neutral particle, that is, its charge is zero. But experiments were carried out in which they tried to measure the charge, or rather, to determine the upper limit for it and I needed to review them. And I coped with this task more or less successfully and as they say in aggregate, I received an offer from the Laboratory Directorate to remain there as an intern. I agreed with pleasure and since then (since 1968) I have been a FLNP staff member, which I have never regretted for.

One of my vivid memories of those years, of course, is quite extensive communication with F.L.Shapiro. His hallmark was his almost constant concentration. It was also manifested in the fact that at any time, in any situation, he could call and start asking about some specific matters - what the situation was, what we managed to understand, what problems still remained and others.

Choosing a scientific specialization

The problem of choosing what to do in science that arises before yesterday's student is very difficult and naturally, very important, since it actually determines the fate of the scientist for many years. Often the choice occurs by chance, under the influence of circumstances that have little control over us. Sometimes, it is possible to follow one's own interests, although this case is very rare, since interests are still too vague. It is important to listen to the advice of older comrades. For me, it happened somehow in a complex way. Having worked for two years in the group of Yu.A.Aleksandrov, all this time engaged in measurements of the amplitude of the n-e interaction, having already published a couple of articles in scientific journals (an article based on research paper was published in the journal Nuclear Physics), I had to abruptly change the topic of my paper.

It happened this way. After completing a two-year internship, I worked at FLNP as a junior researcher and everything went quite well, but in the summer of 1970, I was drafted into the Soviet Army as a so-called two-year student, that is, a lieutenant in one of the air defenses regiments on the border with Turkey. It was not possible to make an excuse, although FLNP Director Academician I.M.Frank wrote all the letters required in such cases and we went together with another "victim", my friend from my student days and for the rest of my life BLTP staff member Slava Priezzhev along the route Dubna - Moscow - Baku - Tbilisi - Yerevan - Echmiadzin. Why was the route so difficult? Because the orders we received in Dubna stated: to report to the headquarters of the Baku Air Defense District. We showed up, but we were told that we were not needed in Baku, but were needed in Tbilisi and we had to report there to the corps headquarters. We showed up and they told us - well done, but you are not needed in Tbilisi, you are needed in Yerevan and you need to report there to the regimental headquarters. So, having traveled (and walked) through all three Transcaucasian capitals, we found ourselves in a regiment the headquarters of which were actually located next to Echmiadzin. When asked to send us to serve in one division, the chief of staff of the regiment, wringing his hands, explained that this was in no way possible, because there was one place in the 2nd division and one - in the 4th. After that, six more two-year students arrived in my 4th division and about the same number - in the 2nd. We can talk endlessly about our two army years... Many years later, Slava and I sometimes continued to recall all sorts of episodes from our two army years, for a long time we called each other "lieutenants" and certainly did not consider these years lost.

When I finally returned in mid-summer, 1972, another conversation took place. Fedor Lvovich was already seriously ill at that time, he had undergone a complex operation, but for a while, he felt better and invited me to come to his home in a cottage on the Chernaya Rechka. We were sitting on the balcony, looking at the forest and Fedor Lvovich explained to me that with n-e interaction, that is, with the paper under the supervision of Yu.A.Aleksandrov, I should "give up" and go to work in the new department of Yu.M.Ostanevich that was being established at FLNP and to develop the technique of structural neutronography there, in order afterwards to study the structure of biological molecules at the IBR-2 reactor. The main argument was that I had already mastered the neutron diffraction technique by measuring the scattering lengths of tungsten isotopes. All my objections - the fact that I am not a solid-state scientist by training and that I know nothing about biology and that in fact I clearly don't understand enough about diffraction - were listened to, but rejected. I must admit that I really liked neutron diffraction as an experimental technique. I realized its enormous potential, especially when used on a pulsed neutron source. In addition, the strict mathematical validity of the technique was attractive that allowed to interpret experimental data much more clearly than, for example, in small-angle neutron scattering or reflectometry. After thinking about all this, I decided not to resist, to start working and then to see what comes of it all. After several years, it turned out that it worked well, we succeeded to develop a very good diffractometer and to carry out a range of interesting experiments on it. Most importantly, it was possible to show in practice that the prospects for the development of this technique in Dubna, at the IBR-2 reactor, as I.M.Frank and F.L.Shapiro believed, are truly impressive.

What happened?

My supervisors I.M.Frank and Head of the Department of Condensed Matter Physics Yu.M.Ostanevich understood that alone in developing a new technique at FLNP one could not advance far and they willingly responded to requests to transfer or to hire one or another employee to the group. Gradually, a completely combat-ready team was developed and by the start of operation of the new powerful IBR-2 reactor in 1982, we were already quite ready for big things. The group was international from the very beginning; over the years, employees from Romania, the Czech Republic, Poland, Mongolia, Korea and Vietnam worked in it. We maintained friendly relations with almost everyone, we maintain correspondence and sometimes, we manage to see each other. This is not surprising for JINR; physicists from the Member States in those years were glad to come to work in Dubna. Today, long-term (more than a year) visits have become noticeably less frequent; they mainly come to implement experiments for one to two weeks. The number of such short visits especially has increased with the start of operation of IBR-2 and the development of several high-class neutron diffractometers on it. Over the years, in addition to colleagues from the Member States, whoever has come to us. We have carried out experiments with physicists from Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Japan, USA, Portugal, Spain and other countries. Gradually, our group has turned into a sector, that is, a department consisting of several (now five) groups. By the mid-1990s, mainly thanks to the efforts of this staff, several specialized neutron diffractometers were put into operation at IBR-2: DN-2 - a multifunctional diffractometer with a record aperture ratio, HRFD - a Fourier diffractometer with a record resolution, DN-12 - a diffractometer that allows to study small-volume samples, mainly, at record high external pressures, SKAT is the world's best diffractometer for studying coarse-crystalline textures, FSD is the best diffractometer in Russia for studying internal stresses in bulk engineering products. Much of this work was carried out in close collaboration with other well-known neutron centres in Russia - the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow and the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Gatchina.

Since 1991, senior students not only from Moscow State University, but also from other universities in Moscow, Tula, Tver, Nizhny Novgorod, Krasnoyarsk have been trained at FLNP... Many of them then completed postgraduate stu dies and remained to work in the Laboratory. The group of physicists working at FLNP diffractometers is well known in the scientific world; in particular, large Russian and international projects are constantly carried out on the most pressing topics. Moreover, we can confidently say that in terms of the totality of their capabilities, the facilities for neutron diffraction in Dubna are currently one of the best among all neutron laboratories in the world. It all started more than 50 years ago, when Fedor Lvovich said that he and Ilya Mikhailovich had come up with an interesting topic for me to work on.

Photo from the archive of A.M.BALAGUROV