Electronic english version since 2022 |

The newspaper was founded in November 1957

| |

Their names are in the history of the Institute

"Knowledge of physics is the ability to solve problems"

"Knowledge of physics is the ability to solve problems"

A new book has been published in the JINR Publishing Department. It is dedicated to the famous theoretical physicist Gari Efimov (1934-2015), whose entire scientific life was spent at the Laboratory of Theoretical Physics. The book is compiled by BLTP chief researcher Mikhail Ivanov and JINR Chief Scientific Secretary Sergey Nedelko. We are presenting to our readers fragments of this book - two chapters written by Gari Efimov.

About my teachers

If a teacher is truly wise, he will not command you to enter the house of his wisdom; rather, he will lead you to the threshold of your mind.

D.H.Gibran

Of course, the 70th anniversary (memoirs were written 20 years ago - Ed.) is quite a decent reason to start summing up my activities, but I will arrogantly wait to do it until a more significant date but now, I would like to start with it. I once heard that in an old Prussian military manual there was a phrase: "A horse consists of three unequal halves: head, body and tail". Applying this classification to life, we can say that life also consists of three unequal "halves": the first "half" is childhood, education until entering adulthood, when a young man turns into a man, the second "half" is adult life until today and the third "half" is life after today.

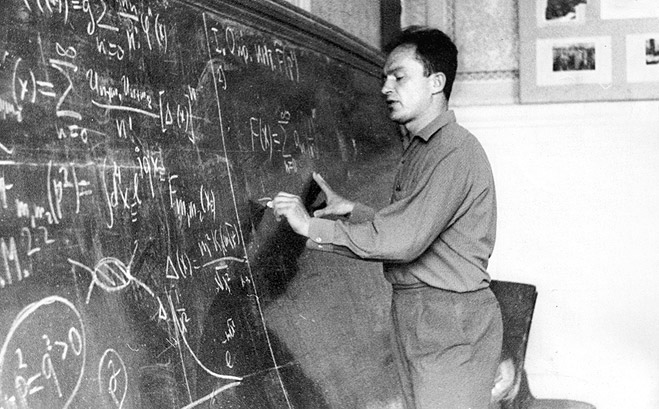

G.V.Efimov. Late 1950s

Here, I will talk about the first "half" of my life until the moment when I felt like a man. In this first "half" of life, teachers play a decisive role, under whose influence we choose our life path and I want to talk about them, my teachers, as well as some memorable events that I witnessed and that give an idea of that life situation, in which my character was developed.

My paternal grandfathers were Kuban Cossacks from the village of Tikhoretskaya and my maternal grandfathers were peasants from the Tula province. My great-grandfather Grigory Ermolaev was personally acquainted with Leo Tolstoy and helped him in his work "on hunger," as they said at the time. My father and mother met in Moscow, where they received a liberal arts education, my father - in economics and my mother - in history and the latter at that time (the second half of the 1920s) was far from safe, since history was directly related to politics. My father began working as an economist in the meat and dairy industry and my mother - as a school teacher. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow in the Kalininsky industrial region near the Perovo station. My family and closest relatives, that are my father's and mother's brothers and sisters (there were seven of them in total) maintained family ties, often met with or without reason and I closely communicated with them and with my cousins. However, it must be said that no one of my relatives was engaged in science.

At school, I studied almost perfectly (in literature I always had a solid B, since I was never able to properly "reveal the image"), mathematics was most easy for me and later, physics. My parents supported and developed in me the desire for knowledge in every possible way, although they could not provide specific assistance in mastering the natural sciences.

Of all my uncles and aunts, Uncle Zhenya, my mother's brother, Evgeny Ermolaev had the greatest influence on me. He was a design engineer that designed and built cannons during the war. He talked to me a lot, told me different stories from engineering life and as a result, technology and the profession of an engineer became very attractive to me. My parents also wanted me to get a higher technical education and become an engineer.

In those days (post-war until the early 1950s), the USSR had a compulsory seven-year secondary education, after which one had a choice: to go to work, to enter a technical school, or to continue studying at a secondary school and then to enter a university. Therefore, children came to the high school classes (at that time there were separate schools - male and female), interested in studying, the classes were strong and of course, an unspoken competition arose between students that knew and could do what better. I did best in mathematics and physics.

Our class teacher Nikolay Vinogradov, that is also a mathematics teacher, singled me out from other students and monitored my studies. I remember his one categorical advice. In the ninth and tenth grades, some of our schoolchildren began to independently study higher mathematics and use terms like integral, derivative, others that impressed the rest; I, in particular, began to feel inferior, although I understood school mathematics. Nikolay Vinogradov, when I asked him whether I should also start studying higher mathematics, categorically objected: "No! You will probably understand something incorrectly and in high school you will have to relearn it, as a result, you will lose a lot of time. It's better to solve as many problems as possible, find collections of problems to prepare for various universities and solve them from cover to cover". That's what I did. Subsequently, I became convinced how correct this advice was. Nikolay Vinogradov encouraged me to go to Moscow State University to study mechanics and mathematics. However, I did not want to enter Moscow State University, because at that time, we were convinced that Moscow State University produced either scientists or school teachers. I wasn't sure that I would make a scientist, I didn't want to be a school teacher, but I was convinced that I would make a good engineer.

The second teacher that had a great influence on me was our physicist Nikolay Shevlyagin. From him I first heard that knowledge of physics is the ability to solve problems. He constantly repeated to us: "The best textbook on physics is Znamensky [Znamensky was the author of a collection of problems in physics that we used at that time]. And if you want to know physics, you should solve all the problems from the first to the last." I took out various problem books and tried to solve them "from cover to cover".

By the beginning of the tenth grade, I had already attended open days at many universities in Moscow and I had made a decision of entering the Bauman Higher Technical School. But afterwards, I accidentally came across Korsunsky's popular science book "The Atomic Nucleus". I read it like a detective novel and decided that I would be an engineer in the nuclear industry. But the problem arose of finding such a university. In those days, everything related to nuclear physics was classified and in my immediate circle there was no one that knew where the institute I needed was located. I started searching and it turned out that a student from our school one grade older than me, Zhenya Zhizhin (today, he is a professor at the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute) studies at the Moscow Mechanical Institute and this institute produces nuclear industry engineers. Zhenya gave me complete information and without any problems (I knew how to solve problems!) I became a student at MMI in the autumn of 1952.

The first thing that puzzled me at the Institute was higher mathematics. The lectures were based on Fichtenholz's university course, starting with Dedekind's sections. The first lectures passed me by. To my surprise, I discovered that I understood nothing. Then I sat down with Fichtenholz and for the first month did practically nothing except mathematics. Finally, it dawned on me that higher mathematics is a different language and a different system of concepts compared to school mathematics. After this "discovery" everything became extremely clear and even obvious. Aleksey Petrov that unfortunately passed away early (he had tuberculosis), taught us mathematics and held seminars in our group. His manner of lecturing should be specially described. His lectures showed us that mathematics is a living science. Here, he formulates and proves another theorem. Then, he says: "I made a mistake in proving the theorem. Where is it?", or: "If this condition is omitted from the formulation of the theorem, then where does the proof of the theorem fail?", or: "And why won't this proof fail?" and gives an alternative system of reasoning. It so happened that I was almost always the first to answer such questions. Alexey Petrov paid attention to me, invited me to his house, where we discussed various aspects of set theory, to the investigation of which he wanted to involve me, but abstract logic did not attract me, I was closer to what could be "touched with my hands". For me, Alexey Petrov was the first teacher that introduced me to the world of big science.

Hiking as a means of education

I have often had and still have to participate in debates on the topic: how to combine work, leisure and raising children. The fact is that any person whose creative work takes up all his working and non-working time is always reproached that he abandoned his family, that his children became homeless and so on. And really, how to combine all this? Of course, each person solves these problems in his own way. In this note, I would like, as we usually write in newspapers, to "share my experience."

When my children began to more or less grow up, pretty soon they began to ask me: "Dad, what are you doing?" Since I worked on quantum field theory, I naturally couldn't tell my children anything intelligible about my work.

However, the question arose: where and under what conditions can parents and children, just beginning to understand the world around them, live with the same, mutually understandable problems? And for myself I decided: on a good hiking trip. When children are still small, it's a kayak and then mountains, where children can be taken almost from the age of six or seven.

In a good camping trip, everything is done seriously: a fire is not for fun, but for cooking, tents for sleeping, work even in bad weather and so on. Children instantly understand that all this is not a game, this is life in which they accept their feasible and most active participation. They see their parents in a job that they understand. And here arises, of which I am convinced, the closest understanding of each other. In this work, children very quickly become independent and most importantly, reliable people.

No rest house can replace daily work side by side with your children. Since people come to rest houses with everything ready, contacts with children are much weaker than on a camping trip. And for me, there was and is no greater pleasure than watching children from the sidelines when, on a hike, they heatedly discuss something, play some of their own, independent games, or participate in some responsible work that is necessary for everyone. When you return home, you can come home from work even later; summer impressions last a very long time. And the children have questions about where we will go on vacation in the winter, where we will go in the summer, with whom, so on. And plans begin to be born...

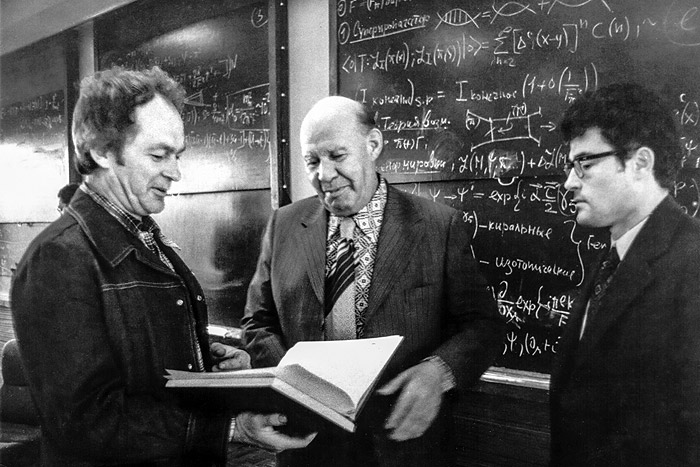

G.V.Efimov, D.I.Blokhintsev, V.N.Pervushin. Late 1950s

Grandmaster B.V.Spassky is holding a simultaneous game session at the JINR Club of Scientists.

G.V.Efimov at the chessboard, 1962

40 years since the publication of the book by N.N.Bogolyubov and D.V.Shirkov "Introduction to the theory of quantized fields".

From left to right: B.A.Arbuzov, B.M.Barbashov, D.V.Shirkov, V.A.Matveev, G.V.Efimov, 1998