Electronic english version since 2022 |

The newspaper was founded in November 1957

| |

|

Number 11 (4759) |

Seminars

Women that changed nuclear physics

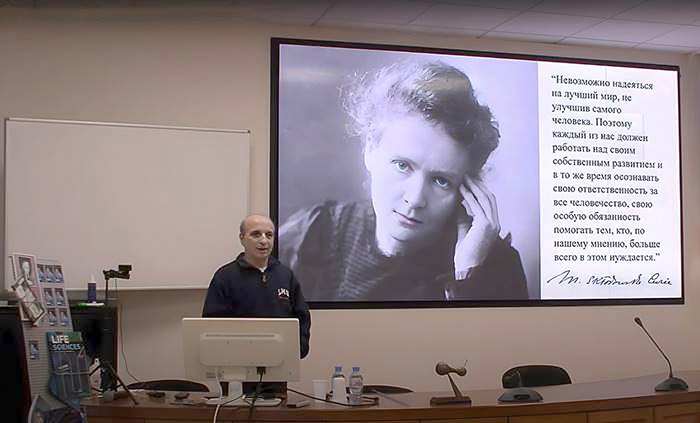

On 12 March, a seminar of the Division of Nuclear Physics was held at FLNP, at which Ivan Ruskov (Institute for Nuclear Research and Nuclear Energy of Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, FLNP JINR) gave a lecture "Pioneers of Nuclear Physics: Women that changed science".

The idea to give this lecture was inspired by the International Women's Day on 8 March and the bright destinies of outstanding women physicists, whose scientific research and discoveries had a significant impact on different areas of neutron and nuclear physics. The lecturer began his speech with the statement of Lisa Meitner: "Science allows people to unselfishly try to find truth and objectivity; it teaches people to accept reality with surprise and admiration. And not to forget the great reverence and joy that the natural order of things gives to the true scientist". Of course, in the lecture, women's fates were embedded in the general history of the development of science, with possible and failed discoveries, competition between countries in atomic projects.

We heard and were able to compare well known and quite unfamiliar biographies of amazing women - women that had a hard time getting an education, that selflessly and persistently made their way into science, that were often unfairly deprived of awards, that founded departments and entire institutes that still function today, that died of cancer caused by radiation but most importantly, that left a bright trace in science. Maria Sklodowska-Curie that was awarded two Nobel Prizes - in physics (together with P.Curie and A.Becquerel) and in chemistry, is a bit out of this rule.

Romanian Stefania Maracineanu worked at the Radium Institute with Marie Sklodowska-Curie that gave her the opportunity to deepen her knowledge and skills in radiochemistry. Returning to Romania, she established the first laboratory for radioactivity research there.

Lise Meitner became the second woman in the history of the University of Vienna to be awarded a doctorate in physics and the first female professor in Germany. She gave a theoretical explanation of nuclear fission, but although nominated for the Nobel Prize 48 times (29 in physics and 19 in chemistry), she never won it.

Toshiko Yuasa was the first female nuclear physicist in Japan and worked in France and Germany. After the surrender of Germany, she had to return from Berlin to Japan via Siberia, carrying the double-focus beta spectrometer she had designed on her back.

Elizaveta Karamihailova is Bulgaria's representative in the small group of women pioneers in the field of nuclear physics. She was the country's first female nuclear physicist, a doctoral candidate at Sofia University and the first to be awarded the title of professor. She founded the Department of Atomic Physics at Sofia University and the Laboratory of Radioactivity at the Institute of Physics, BAS. Her research on radioluminescence of the mineral kunzite became the basis for advanced dosimetry techniques. Elizaveta worked at the Vienna Radiological Institute, where she collaborated with Marietta Blau in the investigation of polonium and thorium neutron bombardment techniques and afterwards, worked at the Cavendish Laboratory under E.Rutherford (the first centre for radioactivity research in the early twentieth century was the M.Sklodowska-Curie Radium Institute in Paris). Her doctoral thesis (1939) was the first publication on nuclear physics written by a Bulgarian in Bulgarian and the future academician, Director of the INRNE BAS and Vice-Director of JINR Hristo Ya. Hristov started his scientific path as a laboratory assistant to E.Karamihailova.

Maria Goeppert Mayer started working on her thesis on "Elementary processes with two quantum jumps" while studying at Cambridge University and defended it at the age of 24. After moving to the United States with her husband, she first took care of their two children, afterwards, began teaching at universities without pay and together with her husband, wrote several articles on physical chemistry. In 1940, the family moved to New York, where Maria continued her research with E.Fermi.

In 1942-1945, she participated in the Manhattan Project, working on the separation of uranium from ore and cooperated closely with E.Teller. Maria was the first to investigate the phenomenon of double quantum emission and double beta decay, the first to study the atomic properties of transuranic elements. Together with J.Jensen, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 for her shell theory of the structure of the atomic nucleus.

Chien-Shiung Wu was a prominent American nuclear physicist of Chinese descent and a participant in the Manhattan Project. In 1944, she started to work at the Laboratory for Substituted Alloys at Columbia University that focused on uranium enrichment using gas diffusion. Her investigation of radioactive isotopes of xenon in 1940 played an important role. E.Segre remembered her when the nuclear reactor recently constructed at the Hanford site was shut down and put into operation at regular intervals. It turned out that it was the fault of xenon-135 that had an unexpectedly large neutron absorption cross section.

In November 1949, Chien-Shiung Wu experimentally verified A.Einstein's mental experiment on quantum entanglement, establishing the phenomenon and validity of entanglement using photons by observing their angular correlation. Her experiment was the first important confirmation of quantum results pertaining to a pair of entangled photons applicable to the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox. After the war, Chien-Shiung Wu taught at Columbia University, becoming the first woman full professor at that university. In 1956, her fellow theorists Ts.Lee and C.Yang asked her to carry out an experiment to test the parity law. She carried out a series of experiments showing that atoms have a preference for the direction of rotation. The results stunned the scientific community and Lee and Yang were later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, while Chien-Shiung Wu was not included among the nominees. Her book "Beta decay" published in 1965 is still a board book for nuclear physicists.

Zinaida Ershova graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow State University in 1930 and began working in the radium shop of the Moscow Rare Element Plant, where the first radium was produced the following year. In 1936, she was trained at the Radium Institute in Paris under the supervision of I.Joliot-Curie. Having headed the laboratory in Giredmet, she developed the technology of obtaining carbide and metallic uranium for the design of the first experimental reactor F-1, as well as metallic plutonium, polonium and tritium. Her laboratory produced the first 73 micrograms of plutonium. Focusing on polonium, Z.V.Ershova developed a technology for "wet" production of polonium from irradiated bismuth. Polonium obtained at the new facility was used in the first atomic bomb. In 1952, Zinaida Ershova, a Candidate of Chemical Sciences, was awarded the degree of Doctor of Technical Sciences without defending her thesis. In the early 1960s, polonium was excluded from atomic weapons but began to be used in isotopic sources of heat and electricity. Z.V.Ershova began to develop a new area - the chemistry of solid polonium compounds that were later widely used in the Cosmos satellites and in the first lunar rovers. Zinaida Ershova is a thrice winner of the Stalin Prize of the second degree and the V.G.Khlopin Prize of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

These are not all the female stars of nuclear physics, whose fates Ivan Ruskov told the participants of the seminar about in his speech. He ended his speech with a statement by Marie Sklodowska-Curie: "It is impossible to hope for a better world without improving the human being himself. Therefore, each of us should work on our own development and at the same time realize our responsibility for the whole of humanity, our special duty to help those that in our opinion, need it most.

Olga TARANTINA